Palestine

I ended up in a gorgeous hilltop village called Jayyous in the West Bank of Palestine for six weeks. I had a brilliant time and made some great friends, including a 20-year-old Palestinian who had studied a year and a half in Rostov, Russia. Some of the villagers were fairly conservative, but he and I could talk about anything we wanted in Russian.

I taught English to smart, funny teen-aged Palestinian girls for a Canadian NGO called Project Hope. A Palestinian woman my age named Abir was my partner, and after class I often secretly shuttled love letters between her and the man she wanted to marry.

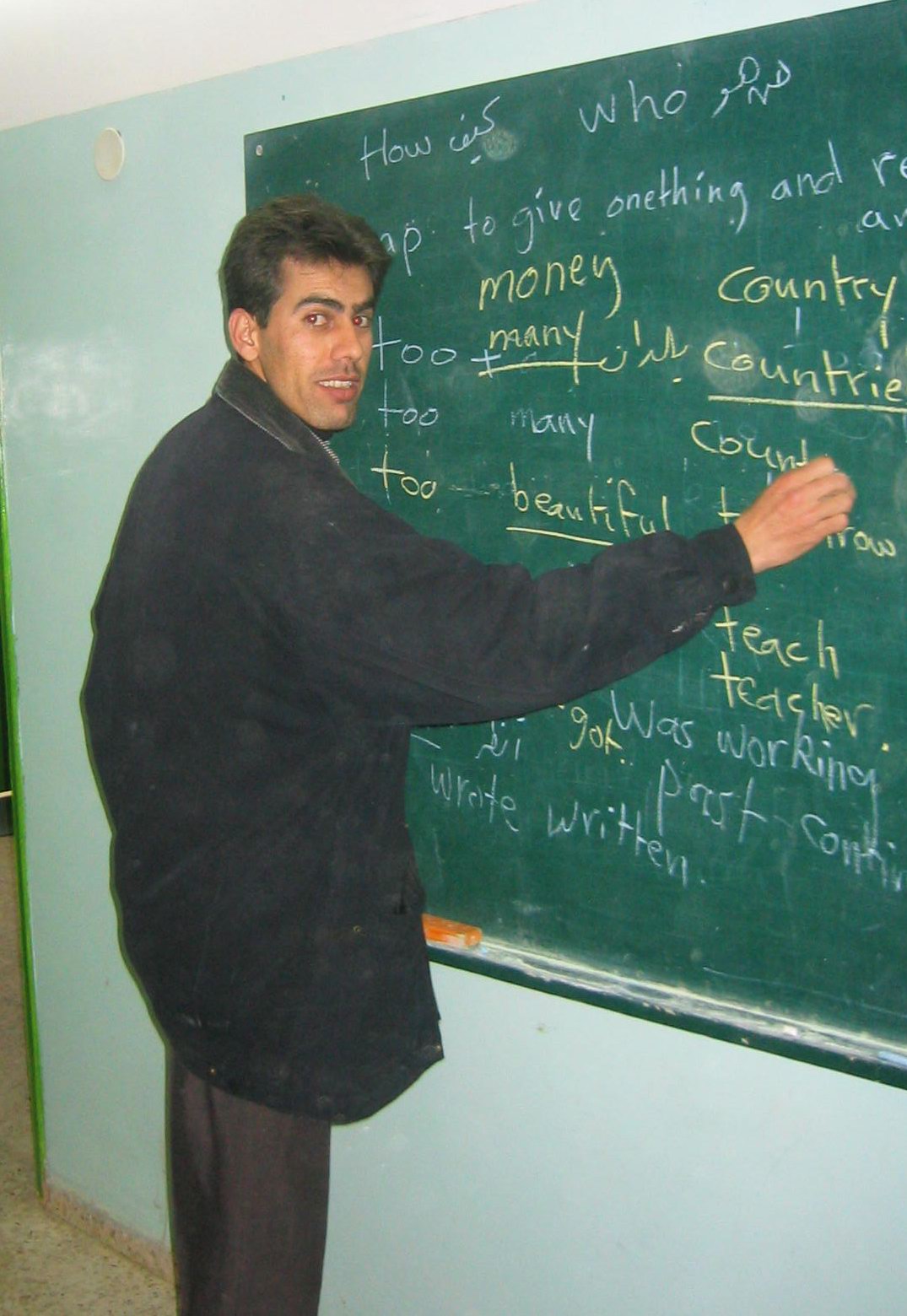

Abir teaching some of the girls

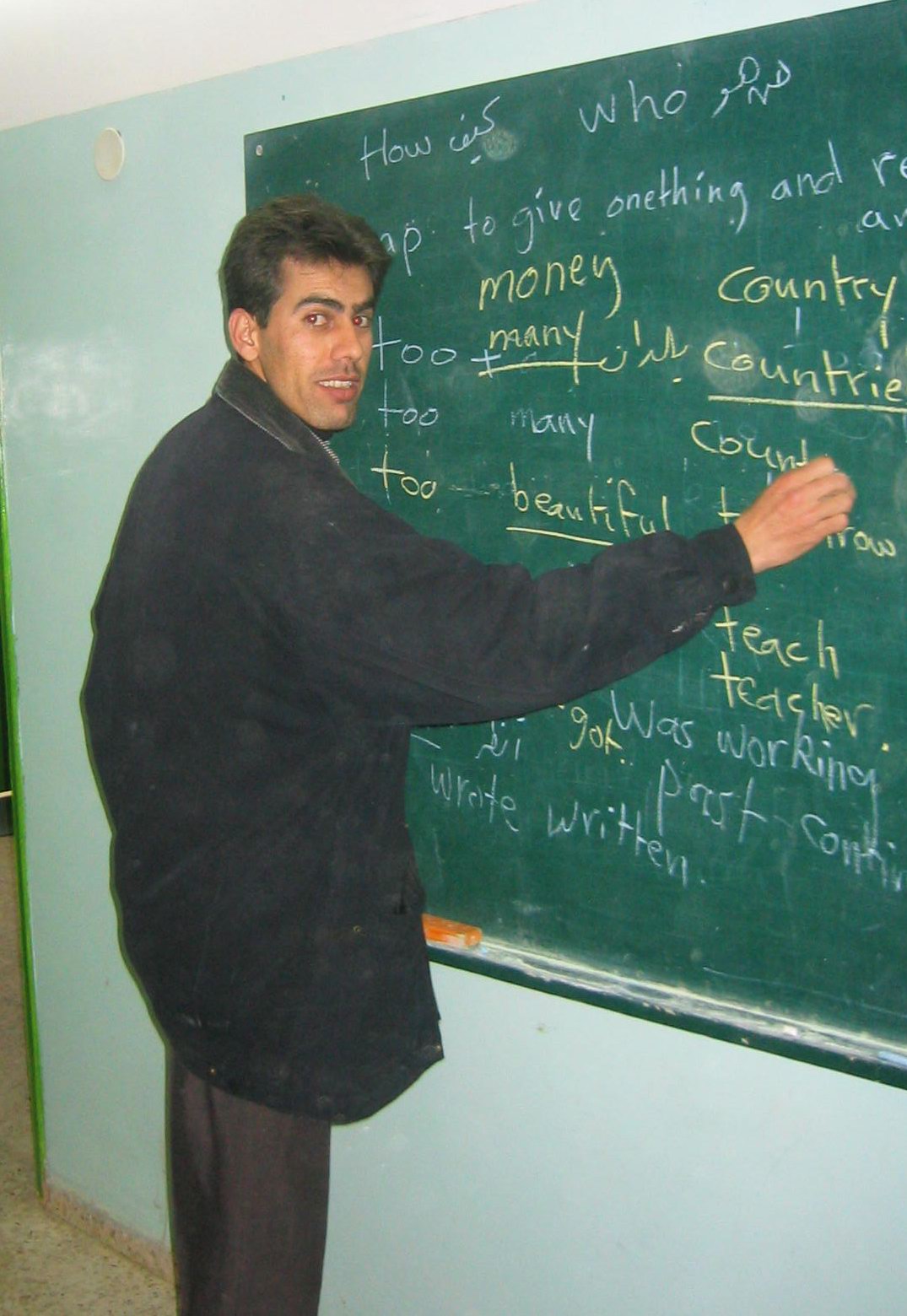

Rasim, another of Project Hope’s teachers

I watched CNN and al-Jazeera and smoked nargila and talked for hours almost every night with two brothers named Hakim and Hakam and whoever else happened to stop by. By the time I left the village, I was calling them ‘brother.’

I lived with a family that had two small children, and among our neighbors was the Mayor of the village, a charming old patriarch named Fayez. He had a son my age named Mohamad who was at least as charming as his dad. His daughter, named Azhar, was about 13 years old, and it was strange to see her worried about normal 13-year-old girl things, but also being so strong and brave and kind, and having to face up to all the difficulties her family and village were enduring.

In the six weeks I lived in the besieged village, where people were cut off from their land and water, not allowed to come and go without special Israeli permission, patrolled constantly by armored Jeeps, and harassed in the dead of night by young soldiers, there were no more than two nights that I wasn’t invited to dinner at somebody’s house. Their hospitality was outstanding, and most of their company delightful.

But dispersed among some of the pleasantest hours I’ve spent, I and friends of mine witnessed brutality and humiliation I had not previously dreamt of. Abuses by Israeli soldiers were pandemic and horribly demoralizing. Every time someone left the village, they could be arrested at a checkpoint without charge or trial and held indefinitely, a practice called ‘administrative detention.’ And that wasn’t the worst that could happen by any means. Knowing that my tax dollars were funding the Israeli occupation to the tune of millions of dollars per day for the past 50 years made it even worse.

Ronan, too, had seen the worst brutality done or funded by Western powers in Timor, Lebanon, and now Iraq, and he said it was a shattering bit of education.

Journalists who’ve reported from war zones all over the world say they have never encountered such rough treatment as they are receiving from the Israeli army. According to more than one eye-witness account I’ve heard or read, not counting Ronan’s, children are sometimes shot for sport by IDF forces.

Rachel Corrie, an American activist, was run over by a bulldozer and killed when she tried to prevent the demolition of a Palestinian home in the southern part of the Gaza Strip. A young British photographer, Tom Hurndall, was shot in the neck and killed when he tried to protect some children from sniper fire in Gaza. The Japanese nurse I met in Amman told me about seeing apartment blocks bombed by Israelis with American-supplied jets in Gaza at rush hour, killing children on their way to school under the pretense of ‘counter-terrorism.’

Two of my friends, an American and a Canadian, were arrested without charge by Israeli soldiers and used as unwilling human shields in the town of Nablus, West Bank. They were then taken into an occupied Palestinian home that had been trashed, with feces smeared all over the bathroom, and they were ‘jokingly’ threatened with a loaded machine gun pointed at the American girl’s head.

The leader of a Canadian educational NGO in Nablus, a Palestinian woman in her early twenties, recently had her house occupied and trashed, her little nieces injured by smoke inhalation from the bombs the Israelis used, and an unarmed passerby shot by an Israeli soldier from her own window.

In the West Bank, we saw people’s land and water resources being systematically stolen by what many in the international community call the Apartheid Wall and Israel calls the Security Fence. According to an Israeli source, it is “a 60- to 100-yard-wide combination of barbed wire or chain-link fences, ditches, roads, 25-foot-high concrete walls, concertina razor wire, watchtowers, cameras and electronic sensors” and intended to span 720 kilometers, mostly well within the internationally accepted 1967 borders of the West Bank. (Map of current and proposed layout.) The network of walls and fences cuts Palestinian people off from their land, water resources, families, communities, schools, hospitals, and livelihoods. A town called Qalqiliya with 40,000 residents has a wall as large as the Berlin Wall built all the way around it with only one gate, which is controlled by the Israeli Defence Forces. It has effectively been turned into a giant prison.

Israeli settlements are visible in every direction around the village where I lived, and a Palestinian man I know has sewage from an Israeli settlement regularly dumped into his fields. I had to reassure children when tanks went by their houses, helicopters carrying visible bombs flew overhead, or a car backfired in town. Little boys, with precious little else to do, would sometimes ‘ambush’ armored Jeeps as they patrolled the Separation Fence and throw rocks at them. They usually got tear-gassed in return.

The wife of Fayez, the Mayor of Jayyous, a strong and proud woman, cried like a little girl one day after we had enjoyed a long day picking olives. Nearly every villager who could get past the Israeli checkpoint at the gate of the Fence was there. (Thirteen square kilometers of the villagers’ land now lies behind the Fence on the Israeli side, so now they need special Israeli permission to access their own land.) We enjoyed the day like she had enjoyed it all her life every fall, and her mother’s mother had also, and so on.

Her husband already lost 90% of his grove, about 750 olive trees with an average age of about 600 years old, to the Fence. They were either bulldozed and destroyed, uprooted and shipped to Israel to be replanted, or isolated behind the fence and de facto annexed by Israel. Now the Fence is cutting people off from what is left of their groves, orchards, greenhouses, wells, and picnic spots, and Israeli pressure to abandon their land is so great that next year she fears nobody will be allowed on the land at all. It will be formally annexed, for all intents and purposes stolen. The mayor’s wife was crying because a delightful, useful, spiritual, communal custom done for centuries could be finished by next season if things continued as they were.

Fayez the Mayor pushing his flirty son Mohamad

away from an Israeli soldier on their own land

The abuses I saw were far too widespread, systematic, and indiscriminate for me to believe they were all and only for Israeli homeland security, nor do I find it likely that the abusers are simply a few bad apples.

I don’t believe Israeli soldiers are worse human beings than anyone else. The Stanford Prison Experiment has suggested that any time a group of people has enormous power over another group of people, an element of personal fear, and a feeling of impunity, the situation tends to lead to abuse and inhumane behavior breathtakingly quickly. Abu Ghraib is a good example of that. After thirty-eight years of building up fear and bad feelings in the Territories, and getting away with more and more abuse, it is not entirely surprising to see things like Israeli helicopters firing into crowds of civilians.

It is sobering to imagine what we don’t see.

It is equally sobering to wonder why the leaders of Israel encourage such abuses by routinely letting their men get away with them, and why we in the West allow these atrocities to happen. Our media is severely biased against the Palestinians, and the U.S. government gives weapons and money and bulldozers to Israel and protects them from international accountability. We claim to have gone to war with Iraq because Saddam violated international law and UN resolutions. But Israel is in violation of more UN resolutions than Iraq ever was.

A distraught party leader in the Israeli government has drawn comparisons between Israel’s policies and what happened to his grandmother during the Holocaust. He fears that “At the end of the day, they’ll kick us out of the United Nations, try those responsible in the international court in The Hague, and no one will want to speak with us.” (An Al-Jazeera report Profiles in Self-Criticism touches on the same story.)

Yaakov Peri, one of four former Israeli Security Service chiefs who blasted the Sharon government’s policies, said, “If nothing happens and we go on living by the sword, we will continue to wallow in the mud and destroy ourselves.”

An ultra-Orthodox Israeli Jew named Yehuda Shaul recently returned from his tour of duty as a soldier in the Israeli forces in Hebron, West Bank. As reported in Haaretz, Israel’s left-leaning mainstream news source, during Shaul’s 14 months of service, he could not bear the moral erosion he saw in himself and his comrades. He organized an exhibit of soldiers’ photographs to bring the reality of the territories home. Other soldiers, also mortified by what they had seen and done, offered their photos and testimonies willingly.

Shaul said, “I think that what we’re doing here transcends politics. It’s beyond politics. It’s a true and honest look at reality.”

I consider these men heroes of Israel. They are willing to take a hard look at themselves and their policies and make sincere efforts at improvement. They want to make sure their country is one they can and should be proud of. I admire their courage and hope that they and the people of both sides can band together to educate people, end bad policies, elect better leaders, and make a good-faith try for peace and justice.

I went home in December with my views of the world shaken to their core. The blow to my faith in humanity was offset by the incredible courage and resilience of the Palestinians I’d met, and by the brave Israelis who went against the common thread to protest the actions of their government. I was unutterably horrified, and yet even more inspired.

I decided to spend the summer and fall of 2004 in Ramallah, West Bank, partly because I wanted to help but mostly because I met so many awesome people last time, and I learned so much and had such a great time. I thought the culture and lifestyle I saw being systematically destroyed was worth preserving, and I wanted to enjoy it for myself while I could. I hope it will be there for many more generations to come.

I will work with al-Mubadara, the Palestinian National Initiative, Palestine’s democratic reform party. The leader of the Initiative, Dr. Mustafa Barghouthi, is a Palestinian who was trained as a medical doctor in the former Soviet Union, received a Masters degree from Stanford University, and has had an outstanding humanitarian career. The Initiative seems to me like the best hope for accountable leadership in Palestine, which I hope can lay a groundwork for peace and democratic nation-building, so people can get on with life.

For Ronan |

Home